” I’m compelled to share…regardless of the reception.”

–Chilly Billy Howell, Moon Lake, MS

What’s in a name?

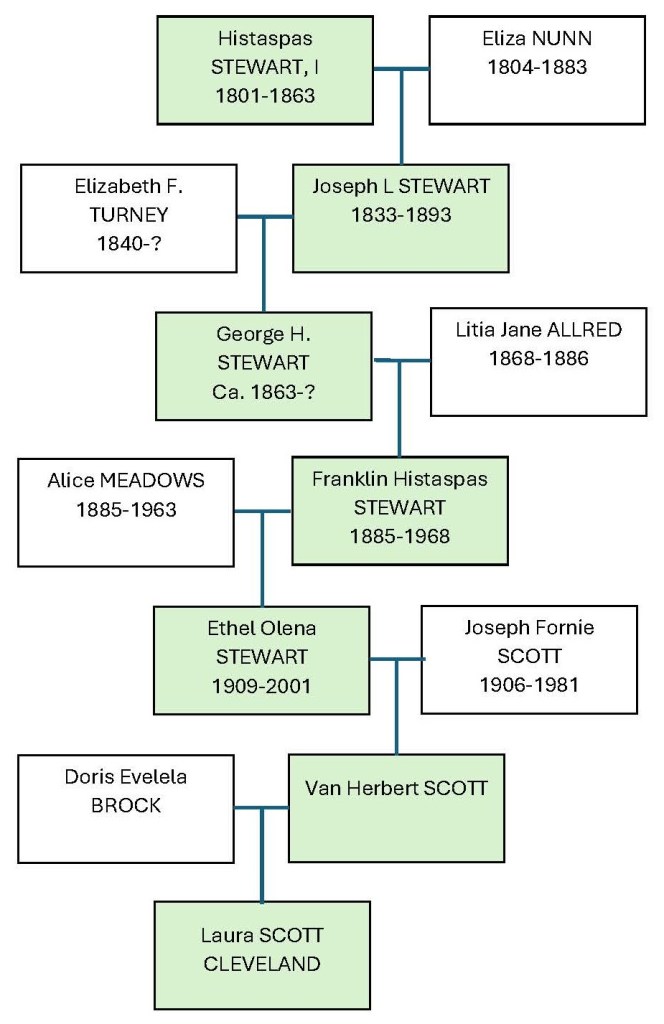

My sympathy is with those ancestry hunters whose surnames are “SMITH.” Verifying their correct “Grandpa John” or “Cousin James” must be the stuff of nightmares. The debut post of FAMILY HEROES and villains in which I shared the events that led to the discovery of my missing 4ggf (fourth great grandfather) demonstrated that a unique name is an extremely helpful clue in confirming that a person is one’s family member. My relatively new cousin Bruce and I may never have connected had it not been for that unique name of our shared grandfather, “Histasperus.”

On Pandemic Time

Everyone in the world remembers the year 2020. Covid-19 sent us all home and time seemed to stand still. To exasperate matters, a medical issue extended my family’s house arrest. What was our escape? Social media. Among the top three apps I used to waste–I mean occupy–my time, was Facebook. I’m not a very interactive member of social media. My “feed” is dominated by posts from historical and genealogical societies, county history pages, Ancestry and FamilySearch groups and recipe pages therefore, that’s what my “algorithm” serves up to me. (Who could have predicted that the word “algorithm” would be become part of our everyday vocabularies?)

One day in 2021, mid pandemic, scrolling through my feed, I saw a post about the Crabb, STEWART, Key, Dotson home in Morgan County, Alabama. Of course, the sight of a family surname, STEWART, especially one of a direct line, grabbed my attention. At the top of the page was a pinned post about the unveiling of a historic marker at the home, coinciding with Alabama’s Bicentennial.

There it was! “Histaspas Stewart!”

I read the marker in disbelief:

“In 1850, prominent merchant Histaspas Stewart purchased the property from the Crabb estate.”

Seeing that name and the tiny bit of biographical information on the historical marker ranks in the top five most exciting moments in all my 30 plus years of family research. Up to that point, my STEWART family had been so elusive, and then in an instant, I was bursting with hope that my lost family was found! Although the spelling wasn’t exactly as I’d known it, I knew that minimally, this man had to be connected to my “Histasperus” STEWART.

Needless to say, I pored over every detail of that Facebook page. The page’s photo albums included images of a 1925 title search listing the heirs of Histaspas STEWART, a gold mine of information! I immediately started exhaustive research of those heirs that continues today. Traditional genealogy begins with yourself, working backward through your ancestors. This situation called for forensic genealogy or reverse genealogy, beginning with ancestors and moving forward. I soon learned there had been 11 children, ten who lived to adulthood. This was going to take a minute!

The “Where”

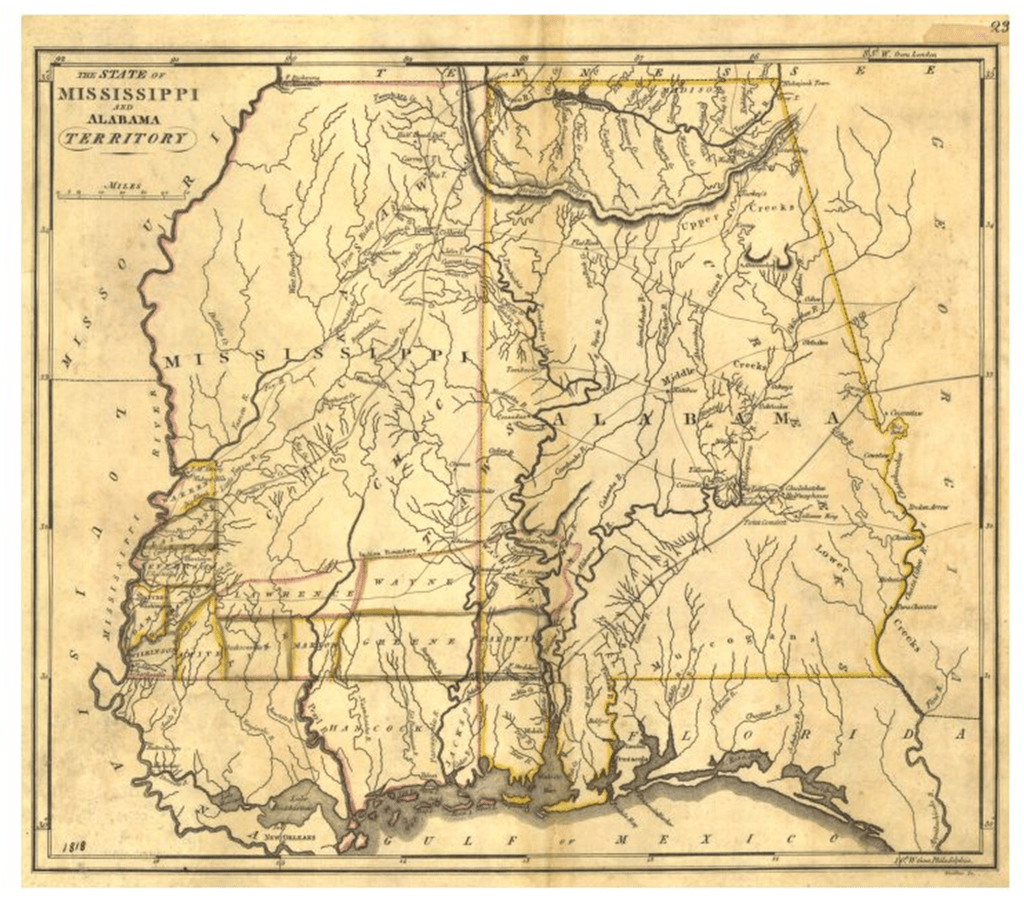

The Cherokee’s cession of their land in Alabama through the 1816 Treaty of Turkeytown2 opened a new “western frontier” situated in what is now north Alabama. Early settlers soon purchased the forested lands and journeyed in the same manner as their adventurous ancestors who migrated through the upper colonies in hopes of better opportunities. Almost exclusively, migration was a cooperative effort of several families and took place during the winter between growing seasons. Ideally the family groups included a carpenter, a blacksmith, a miller, etc. Ahead of the journey, they pared down their belongings to what was required to survive the trip and to quickly establish shelter upon arrival. In most cases everything was loaded onto pack animals and carts, not necessarily because they couldn’t afford wagons but because roads, as we know them, even primitive ones didn’t exist, only trails and paths which weren’t sufficient even for carts in some places, much less wagons. The families journeyed mostly on foot toward their new lives. Once they arrived, second only to constructing shelter, clearing land of trees and rocks was priority to prepare for the life-sustaining crops to be planted in the spring.

In 1817, bending to pressure from white southerners who desired to have a slave state, the Alabama Territory was formed from land in the Mississippi Territory. Occupying the territory were the Native Americans and the earliest settlers who had journeyed from Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia.

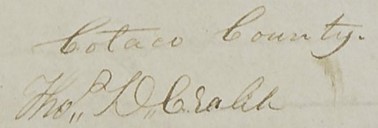

Cotaco County, later renamed Morgan County, in Alabama was formed from the Cherokee cessions in February 1818. Somerville was the county seat from 1818-1891.

On July 10, 1818, five months after Cotaco County was established, Thomas Drane CRABB registered his purchase of 161 acres, near present day Falkville, the property upon which he would eventually build a home. Thomas CRABB became the first sheriff of Cotaco County. He was also one of two representatives from the county who were delegates to the Alabama Constitutional Convention in Huntsville4 in July and August of 1819. They signed the 26-sheet parchment which was adopted on July 30th. On December 14, 1819, Alabama was granted statehood, becoming the 22nd state. Mr. CRABB was the county’s state representative for the remainder of his life.

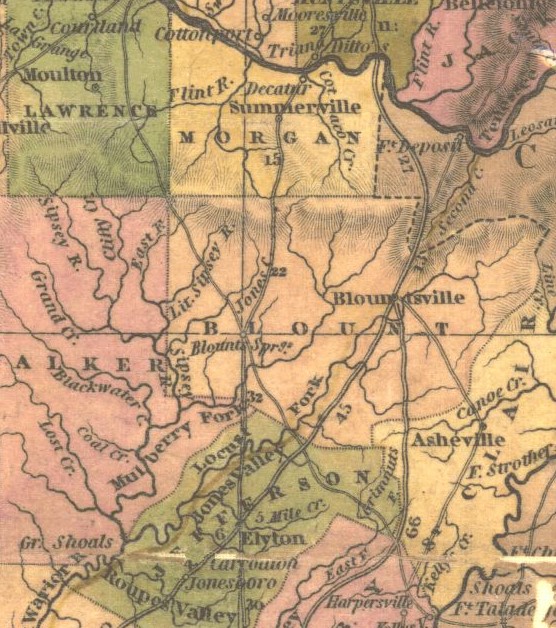

In 1822, four years after frontiersman Thomas CRABB purchased his tract, a man named Abraham STOUT was commissioned to build Alabama’s first north to south running road, from Gandy’s Cove in Morgan County to Elyton, the seat of Jefferson County at that time. Stout purchased land all along the road on which to live as construction of “Stout’s Road” progressed. He set gates to collect tolls that he was allowed to keep as part of his agreement. Over the years as settlements were planted, sections of the road were renamed but there are remnants in Jefferson and Blount Counties still carrying the name Stout’s Road, not to mention, Stout’s Mountain in Cullman County.

Excerpted Civil War correspondence from G.M. Dodge, Brigadier-General [USA], 16th Army Corps, Athens, AL, March 27, 1864, to Maj. Gen. J.B. McPherson, Army of the Tennessee, Huntsville, Ala., describing roads from the Mississippi line to the Coosa Valley:

“Stout’s road runs directly south from Somerville, crossing the headwaters of the Black Warrior…This is an excellent road, well provided with everything, avoids all large water-courses, and is mostly used. It forks near Day’s Gap, one branch leading off by way of Blountsville into Coosa Valley, another to Gadsden; crossing of mountains good.”

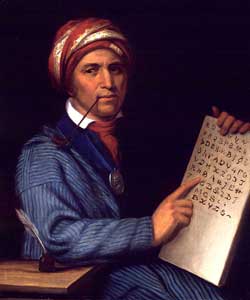

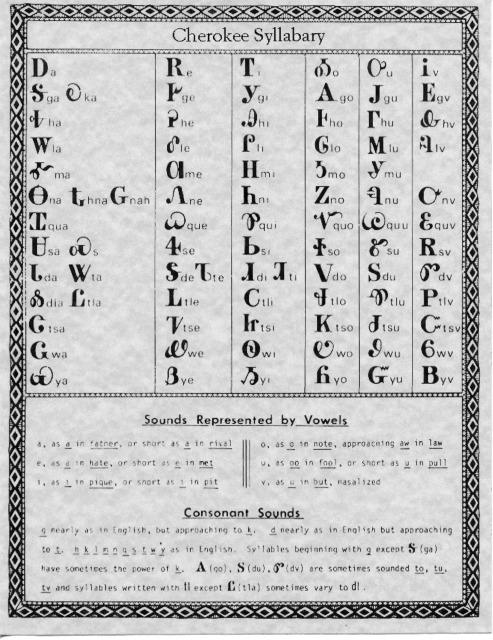

Thomas CRABB’S home stood on Stout’s Road about ten miles south of Somerville, conveniently located next to a natural spring. Glyphs found high on its chimney were studied by researchers at Western Carolina University and determined to be of Cherokee origin and predating Sequoyah’s 1821 Cherokee Syllabary. This finding led historians to speculate that local Cherokees may have constructed or assisted in the construction of the log-framed home. It also narrows the timeframe for the construction of the home to 1818-1821. My own logic causes me to speculate that the stone existed on the property and was chosen by whomever constructed the chimney. Although this theory negates the more narrow timeline, with certainty through documentation, we know that the home was built between 1818 and 1828.

The spring located on Mr. Crabb’s property on this solitary north-south road provided the perfect stagecoach stop. Other researchers have concluded that in its life it had a store and was possibly an inn. Though I haven’t found confirmation that it was an inn in the classic sense, there was the decades-old custom that allowed travelers to stop at any dwelling with the expectation of being fed and housed, as primitive as the accommodations might have been.

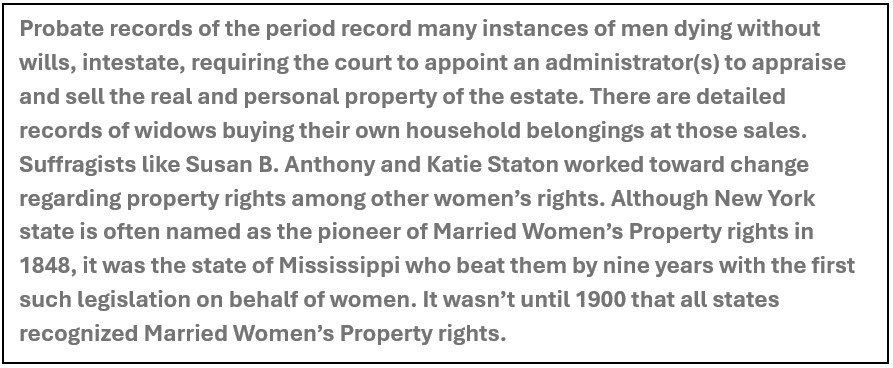

After the death of Thomas CRABB, the home and 160 acres were purchased by Dr. and Mrs. James B. COLLIER in 1830 for $500. In 1837 Dr. COLLIER passed away, without a will, but with a valuable estate. That was a time when women weren’t allowed to own property, with a few exceptions, one being dower’s rights. A husband could legally will one third of his property to his widow in a dower’s portion. In the absence of a will, Mrs. COLLIER was forced to petition the county court for her dower rights which she did. A year later, she was granted possession of one third of the property, including the home.

Not only did women have no right to own property at that time, but they also had no right to custody of their own children. The word “orphan” did not refer only to a parentless child, but also to a fatherless child. When a father passed away, a guardian was appointed for his minor children regardless of whether his wife survived him. This was the circumstance in which Mrs. COLLIER, the lady of the CRABB, COLLIER home, found herself, so Mr. Riley S. DAVIS was appointed guardian for the COLLIER children. I’m unsure which came first, the guardianship or the marriage, but Mrs. COLLIER became Mrs. DAVIS. A dozen years later the COLLIER heirs sold their inherited property to their stepfather/guardian, Mr. DAVIS, who then, in 1853, sold the home and 240 acres to Histaspas STEWART for $900.

The “Who”

Sometime between 1797 and 1801, Histaspas STEWART was born in North Carolina. There is much research yet to do as I have collected few reliable records of his early life. Family Bible records revealed the names of two brothers, Lincoln and Othneal (there’s another great name, it’s biblical!). The first two U.S. Censuses of the 19th century place both brothers in Mecklenburg County. Lincoln lived in Providence Settlement, a section of Charlotte. An unnamed member of Othneal’s household in 1830 fit Histaspas’s age leading me to suspect he resided with his brother, having found no record of his heading a household of his own. Oral history from STEWART descendants suggests Histaspas’s family immigrated from Ireland. One descendant stated his grandfather was a “red headed Irishman,” probably a misnomer. Considering that Charlotte was settled by Scots-Irish Presbyterian (and later in fewer numbers, German) immigrants plus the name STEWART, one can assume the family were Ulster Scots, Scottish people who moved from Scotland to Ulster, Ireland, many moving on to America. So, the “red-headed Irishman” was most likely a red-headed Scotsman whose family eventually came to America by way of Ireland.

When he was a young man, Histaspas migrated to Alabama with another family. To my knowledge the first recorded event of Histaspas’s presence in Alabama was in 1823 at approximately 22 years of age, as he purchased 81 acres which adjoins the present-day Quail Creek Resort in rural Morgan County. Within two years of his arrival in Alabama, Histaspas and Eliza NUNN were married by a Presbyterian minister. Their family grew with the birth of their first child, daughter Mary, on July 14, 1826, who was born deaf and mute. Histaspas and Eliza continued to add to their family as well as amass acreage in Morgan County.

For research purposes it is extremely helpful that these STEWARTS were intent on passing down this unusual name. (Most likely it originated from Hystaspes the father of Darius I and grandfather of Xerxes from the Biblical book of Esther.) To date, among his descendants, I have identified five men and two women who were given a version of his name, one of whom isn’t blood related. To explain the unrelated: Histaspas was appointed guardian of a true orphan, Archibald TAPSCOTT, in 1830. Archibald then named a son “Histaspas Stewart TAPSCOTT.” Two women in the family were given the name “Tassie,” the nickname my great grandfather Franklin Histaspas STEWART disliked so much. It makes one question, when these parents were considering names for their babies, was it the name they loved or the man who carried it? I prefer to think the latter. Besides naming patterns, another advantage to my research was that the STEWARTS were a well-documented family in the rural area of Cedar Cove as well as the city of Hartselle, which was first established as a village in 1870.

The careful study of Histaspas’s children, three sons and eight daughters, revealed that two of his sons served as Justices of the Peace in Morgan County. Interestingly, four of his daughters were born deaf and mute, three of whom never married. Exploring the next generation led me to Histaspas’s grandson George H. STEWART, son of Joseph STEWART (who was NOT involved in public service therefore not as well documented.) Was this “my” George, my 2ggf? As described in my first blog post, my George was a mysterious (nefarious?) character. To confirm if they were the same individual, I turned to DNA. My Ancestry.com DNA results produced two great grandchildren of George H. STEWART genetically matched to me. It was a “Eureka!” moment. These were indeed my grandfathers, my George, my Joseph and my Histaspas. The discovery of the STEWART home through a somewhat random Facebook post coupled with the subsequent research revealed two more generations of my elusive STEWART family. Histaspas STEWART, my 4ggf, raised his large family in the home with the historical marker that stands just 20 miles north of my own home.

Old houses or old places in general evoke indescribable sentiments in me, much like those felt when flipping through old, musty, handwritten pages or ultimately finding new ancestors. Standing on ground where my ancestors walked generations before me strengthens my connection to them–literally grounding. Generally, the only known, much less accessible, common ground to be found surrounds an ancestor’s grave. When the “where” and “who” converged on the ground of my fourth great grandparents’ home, allowing me to walk where they worked and lived their day-to-days, it was a visceral experience. Some will think this sounds a bit crazy. Some will understand it as my “why.”

As noted, Histaspas was acquiring property in Morgan County decades before purchasing the CRABB home and he continued to add to his land holdings for most of his life. About the same time he purchased the home, he donated 20 acres about a mile away on Cedar Cove Road “near Fairview Mountain” for the site of Fairview Presbyterian Church and graveyard. About 1860 on the heels of a “great revival” the church was enrolled in the Tuscumbia Presbytery.

“The past year has been one of unprecedented outpouring of the Holy Spirit in many parts of our beloved country and other lands, so that hundreds of thousands of precious souls have been added to the church.” 8

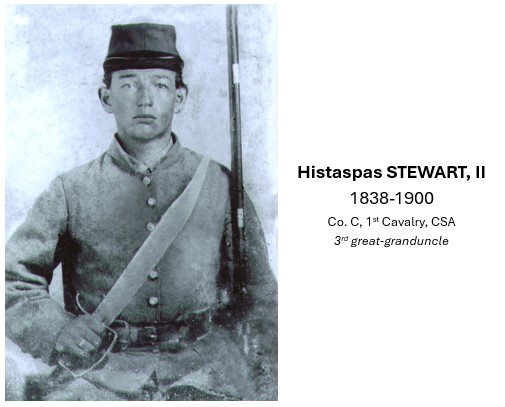

The year 1861 began with Alabama’s secession from the Union. The following year, “the Yankees invaded North Alabama.”8 Of Histaspas and his three sons, I’ve found service records for only one son. One could hypothesize that these men had the means to pay a substitute to take their place in the military, a controversial practice of both the Union and the Confederacy, prompting the label “a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” Histaspas II “Tass,” the youngest son, already a widower at 23 with a two-year-old daughter, enlisted with Confederate Company C, 1st Cavalry in November of 1861. He returned from the war, remarried, grew his family and was deeply involved in the founding, business and civil matters of Hartselle, Alabama. It’s worth noting that a search of the U.S. Federal Census Slave Schedules, listed no members of this family as enslavers, despite their relatively large land holdings, suggesting the practice of sharecropping or tenant farming.

The churches were not immune from North Alabama’s devastation during the war. The Tuscumbia Presbytery’s churches did not have a single meeting from September 1861 to November 1865. In 1903, about 50 years after it was established, “poor interest led to the dissolution”8 of Fairview Presbyterian Church along with seven other churches in the Tuscumbia Presbytery. It is unknown to me how long the Fairview church building was used and when it ceased to exist. All that remains on the site is the graveyard in the woods containing approximately 22 marked and unmarked graves. The last known interment in the graveyard was William T. RHEA in 1910. The names BARNES, BLEVINS, EPPERSON, JOHNSON, LONG, STOVALL and of course, STEWART can be found in the burying ground.

One hundred years and forty-one days before I was born, on May 31, 1863, at the height of the Civil War, Histaspas STEWART passed away at 62 years old, the age I am now. He died intestate therefore his widow Eliza and his eldest son Thomas were court-appointed administrators of his estate. Thomas paid their friend W.T. MORRIS $16 to make a coffin, and his father was the first of the STEWART family to be laid to rest in the Fairview Presbyterian Church graveyard. He was survived by his widow and ten children, with seven of his daughters, including two minors, still living at home. A guardian was to be appointed for the “orphaned” minor daughters.

As the law required at that time, three “independent” appraisers were appointed to inventory and value the estate. Those chosen were closely associated with the STEWART family, one being another 4ggf of mine, George TURNEY, whose daughter was married to Histaspas’s son, Joseph. The estate inventory provides a glimpse of a way of life during a very different time. Partial inventory of Histaspas’s property: 430 acres of land, 3 horses, 1 wagon, 14 head of cattle, 22 head of sheep, 29 head of hogs, blacksmith tools, a cotton gin, a rifle, 6 plows, 3 harrows, debt payable to the deceased in notes totaling $80.25. Apparently, all his cash, $400, was in Confederate notes. We’re more familiar with the term “greenbacks,” the nickname for northern notes. “Greybacks” or “bluebacks,” are nicknames for the Confederate notes, which were worth approximately 33 cents on the dollar in 1863.

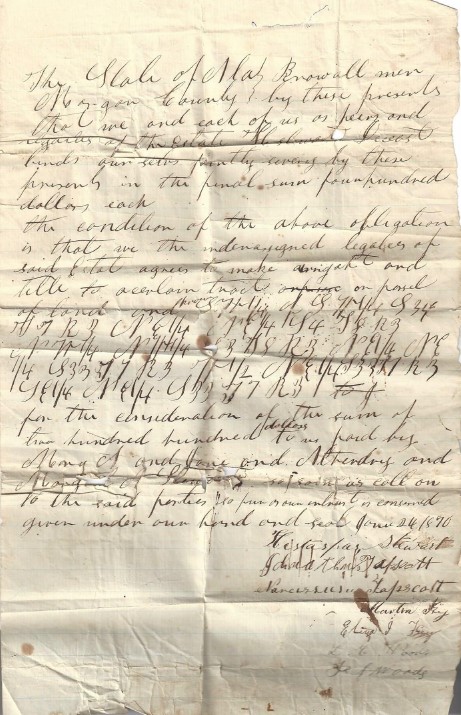

Although an appraisal was completed, the administrators petitioned the court to keep the estate’s property together for a period of five years for the benefit of the four daughters who were “deaf and dumb.” And so, it remained for six years until 1869 when brother Thomas, administrator, once again petitioned the court, but this time to request permission to sell the personal property because it was “an expens and trobel to those to who we have the care.” Within a month a sale of the personal property was held. The proceeds were divided between the heirs, one-fifth share to the widow amounting to $115.17 and $57.57 each for his seven daughters and youngest son. The same heirs entered into a sales agreement to deed 280 acres from the estate to the deaf and mute sisters, Mary, Jane, Atheldria and Margaret Ann, all unmarried and by that time having reached the age of majority. As often was the case, it appears the two elder sons, Thomas and Joseph, had already received their inheritances from their father as they didn’t receive an heir’s portion of the sale, nor were they parties to the land agreement with their sisters. It is known that Thomas had already been gifted land by Histaspas and most likely Joseph had, as well.

Thirty years after the settlement of Histaspas’s estate, sisters Mary, Jane and Atheldria, still lived in the family home and managed the property, even adding to the acreage. In 1902 they deeded five parcels totaling 155 acres to their sister Eliza’s son, nephew Nathaniel “Nat” KEY for “$100.00, paid, and Love and affection for our nephew” with the stipulation that they “shall be permitted to remain on the said premises and have full and free control of the rents and proceeds of the said property until their death, the management and superintendence of the said property however is vested immediately with the said N.A. KEY.” What a deal! The terms “rent and proceeds” from the property lend credence to the idea that sharecropping and/or tenant farming was practiced by Histaspas and then his descendants.

One can assume that Nat KEY moved into the home with his aunts upon his marriage to Nelie MURPHY in 1906. By 1910, of his three STEWART aunts, only his Aunt Jane survived. She was 80 years old and still lived in her old homeplace with her beloved nephew and his family on that section of old Stout’s Road that was renamed Nat Key Road. Jane lived seven more years and is buried in a family plot on the homeplace, Key Cemetery #2. The plot’s first interment was sister Mary STEWART in 1905. Mary wasn’t buried with her family in the old Fairview Cemetery less than a mile away, perhaps because Jane and Atheldria wanted her near to them on the property. Eventually sisters Atheldria, Jane and Eliza the mother of Nat KEY joined Mary there in the cemetery on the homeplace along with approximately a dozen others.

FYI: A burial ground beside a church is a “graveyard.”

A “cemetery” is not associated with a church.

The lovely yet formidable, more than 200-year-old home was occupied by Histaspas STEWART and his descendants for 162 years. It passed from Nat KEY to his son James “Arthur” KEY and then to Arthur’s daughter, Eula KEY. In 2015, my 3rd cousin twice removed, Miss Eula KEY, 82, sold it to the current owners, the Dotsons. She passed away the following year.

Sadly, in the process of writing this post, I learned that Mrs. Dotson passed away early this year. She is buried in the cemetery on the property. The Dotsons researched, rehabilitated and lovingly care for the historical home. I owe them a tremendous debt of gratitude for their preservation of the past, otherwise I may never have found my STEWART family and this rare, amazing piece of my family history, the Crabb, Stewart, Key, Dotson home, that was standing right there UNDER MY NOSE!

Dig a little deeper:

- The Historical Marker Database ↩︎

- Treaty of Turkeytown 1816 ↩︎

- University of Alabama – Historical Maps Collection ↩︎

- Constitution Hall – Constitution Village, Huntsville, Alabama ↩︎

- Crabb, Stewart, Key, Dotson Home ↩︎

- Smithsonian – National Portrait Gallery ↩︎

- Sequoyah Birthplace Museum ↩︎

- James William Marshall, The Presbyterian Church in Alabama, (Montgomery, AL: The Presbyterian Historical Society of Alabama, Donald Carson Graham, 1977, p. 131 ↩︎

- Library of Congress ↩︎

PREVIOUS POSTS:

Share your thoughts?